There’s been an outbreak of impostor syndrome in my social media feeds lately. I’m not going to be terribly specific because I don’t want to embarrass anyone, but I belong to several Facebook groups about writing (fiction writing, academic writing, editing…) and follow several twitter accounts and a few twitter chats on similar subjects.

A common theme over the last couple of weeks has been people wondering if some colossal mistake has been made—the hiring committee wouldn’t have hired me if they knew…; the publisher wouldn’t have accepted my manuscript if…; how could they give me a degree/certification/job? All of these worries stem from the worrier thinking they’ve somehow erroneously achieved whatever it is they’ve achieved. And now the worrier fears everyone will find out the truth—that they aren’t good enough.

When I was researching this topic, I came across several TED Talks on impostor syndrome. I watched four of them: ‘Thinking Your Way out of Impostor Syndrome’ by Valerie Young, ‘Impostor Syndrome’ by Mike Cannon-Brookes, ‘Why Does a Successful Person Feel like a Fraud?’ by Portia Mount, and ‘The Surprising Solution to the Impostor Syndrome’ by Lou Solomon.

The speakers all mentioned the statistic that 70% of people have experienced impostor syndrome at some point in their lives. I, however, have to agree with Lou Solomon when she suggests that number sounds rather low. For the general population, perhaps it’s correct—I have no way of knowing. But for the highly-driven creative types I spend most of my time with, 70% is way too low.

The very qualities that are necessary to be a writer, an academic, or an editor are the same qualities that lead to impostor syndrome. We have high standards, tend to be perfectionists, and care deeply about what we do. I’m not suggesting that you lower your standards or stop caring, just that you find a way to put your inner critic in their place.

The Effects of Impostor Syndrome

Impostor syndrome can cause significant physical, emotional, and professional damage. Near the end of her video, Valerie Young discusses the effects of impostor syndrome. She says it can cause sufferers to ‘fly under the radar’ at work; by this she means sufferers don’t take risks or speak up. They don’t want to draw attention to their perceived imperfections, but in the process they don’t call attention to their strengths, and they risk being overlooked for promotions.

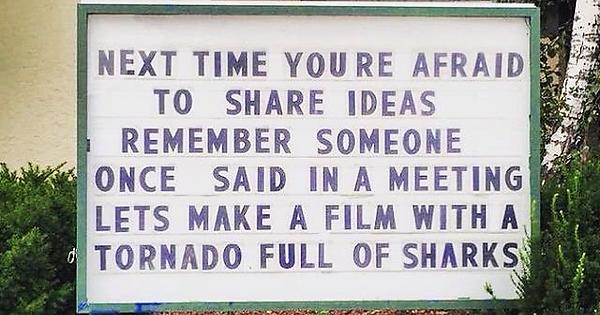

This image made the rounds of a few of my social media feeds; try to remember it the next time you’re struggling to speak up:

Impostor syndrome, according to Young, can also be responsible for procrastination. The logic of the syndrome can be ‘if I don’t do anything, I can’t fail at anything’. Of course we all know this only works in the short term, but if you’re just trying to avoid the negative feelings brought up by the syndrome, that can be enough.

Young also links impostor syndrome to workaholism. Lou Solomon and Portia Mount address workaholism as well. In all three talks, the link between workaholism and impostor syndrome is perfectionism. Our education system tends to teach from an early age that it’s good to always have the correct answer, to always present work in the correct way, etc. This becomes a problem, though, when the need to be perfect leads to agonising over insignificant mistakes.

Solomon tells a story about not being able to sleep because of a typo in a memo she’d distributed at the office (in the days before email); she got out of bed, went back to work, retyped the memo, and redistributed it. She didn’t get back to bed until about 2am, but no one knew she’d made a mistake. For a mind controlled by impostor syndrome, that lack of sleep was justified.

Portia Mount describes how impostor syndrome felt to her: “I was unravelling; the more success I experienced the more anxious and insecure I became. Thoughts kept racing through my mind; I couldn’t shut the voices off. I lost weight; I couldn’t sleep. On the outside I looked happy and successful, [but] inside I was dying”. This idea that success worsens impostor syndrome was common to all four talks.

Impostor syndrome doesn’t only effect you at work; it causes problems elsewhere, too. Whether it’s causing procrastination or workaholism, it will be having an effect on your personal life. If it’s making you miserable (emotionally and/or physically) it will affect your relationships.

How Can We Deal with Impostor Syndrome?

Valerie Young suggests changing your thinking—she says the body doesn’t know the difference between fear and excitement. So, when you feel your nerves kick in tell yourself you’re actually excited. She acknowledges that you won’t believe it at first, but in time you will.

I’ve had some success with this in certain situations. When we expressed performance anxiety, my flute professor always told the flute studio to ‘fake it till you make it’. She was right; week after week in studio, I walked onto that stage and pretended I was confident and happy to be there. By the end of my degree, I really felt that way.

Mike Cannon-Brookes takes a different approach. He doesn’t believe one can overcome impostor syndrome; instead, one must learn to use it and to slightly reframe it. He says successful people still experience doubt, but they don’t doubt themselves; they doubt their knowledge and skills—things they can change. Most importantly, he says successful people don’t see asking for help or guidance as a weakness, but as a necessity.

Portia Mount emphasises focusing on facts; you have had some success, so don’t diminish it. She also encourages people to challenge limiting beliefs. Finally, she says we need to ‘talk about it’. We aren’t as perfect as our overly curated online lives suggest; our meals are not always picture perfect, our hair is not always perfectly coifed. Find a time and a place that you can discuss the realities of your life.

Lou Solomon suggests dealing with the inner critic’s voice directly. She says having impostor syndrome is ‘like having a crappy best friend in your head who says mean things’; she’s named hers Ms Vader. She deals with Ms Vader through another internal voice, ‘a radical hero’ she’s named Betty Lou. Betty Lou calls out Ms Vader’s nonsense.

As this list demonstrates, there may be as many ways to deal with impostor syndrome as there are people suffering from it.

What Can You Do About It?

First, remember that you are not alone.

If impostor syndrome is causing writer’s block, try some of the tips I cover in my post and ebooklet on dealing with writer’s block. If it’s keeping you from submitting your work for publication, get someone else’s opinion. The options for finding someone to read your work are endless: a friend who doesn’t sugar-coat the truth, a writing group, an editor, a mentor, a writing coach… Also, follow through on the age old advice—if it’s rejected, send it off to somewhere else as soon as possible.

If you’re a student (undergraduate or postgraduate) and impostor syndrome is making it difficult for you to participate in seminars or conferences, you’ll find some helpful tips in my post on succeeding in seminars. To recap the main points; set small, achievable goals (like speaking once per seminar and building up from there); discuss the issue with your personal tutor or supervisor; seek support from your university’s counselling services; and talk to your GP.

If you’re in an academic post and your impostor syndrome is making it difficult for you to assert yourself in staff meetings or in lectures and seminars, your university likely offers a lot of support options. The teaching support department probably has workshops on running effective seminars and giving lectures. You may have access to confidential counselling (some universities require you to go through occupational health to access this—if that sets off a whole different kind of anxiety, and you can afford it, hire a private counsellor or talk to your GP). Make contacts with academics at other universities (private social media groups are great for this); it may be easier to ask for help from someone you won’t see at the next board of teachers. Find someone you can talk to about this. It’s a common problem, but if feels lonely when you have it.

Editors suffering from impostor syndrome should engage with continuing professional development to keep your skills up to date. Also, remember it is okay to ask for help. My feed is full of editors asking questions about grammar—you aren’t expected to always have the answer; you are expected to know how to find the answer. Often that means asking someone else.

Until next time, happy writing.

Sign up for my Newsletter